SGUK Podcast : Episode 35– Black History Month – Black Tudors

Their Existence & Their Achievements

This weeks podcast is part of Black History Month in the USA. The UK version takes place in the Autumn, throughout October.

As this podcast channel encompasses global issues, and as it is based in the UK, I am honouring the USA Black History month, and covering the UK origin of the channel, by opting to highlight and celebrate the achievements of black people based in the UK around the Tudor period.

The Tudor period was between 1485 -1603. To put this era into perspective consider a few major figures and events of the time. Christopher Columbus was serving up insurmountable destruction on the “New World”. The Transatlantic Slave trade was born. Michelangelo paints the Sistine Chapel. Henry VIII, well you know; doing his thing. Niccolo Machiavelli wrote The Prince, and The Art of War, amongst others, and Elizabeth I became queen.

Now we have a clearer idea of the era, consider this, Tudor England as it turns out was not lacking in diversity as we have been led to believe. The conception of black people only settling in Britain during the 20th Century, the Windrush being the most highlighted so-called influx is a complete misrepresentation of our history. From popular culture at least, we know that there were black people in Roman Britain, serving in the army or as slaves. But there are records which show hundreds, possibly a thousand free black people living and contributing to Tudor society.

Yes! Black people were living in Tudor England and getting paid! Working at many levels of society. The majority were servants, (cooks, gardeners, laundry women) a respectable profession, but there were others, such as entertainers who would dance and play music for the aristocracy.

John Blanke

“John Blanke, the unwitting poster boy for the Black Tudors (although his image is a caricature). Not a lot is known about Blanke but it is believed he came to London around 1501 as one of the African attendants of Catherine of Aragon.⠀

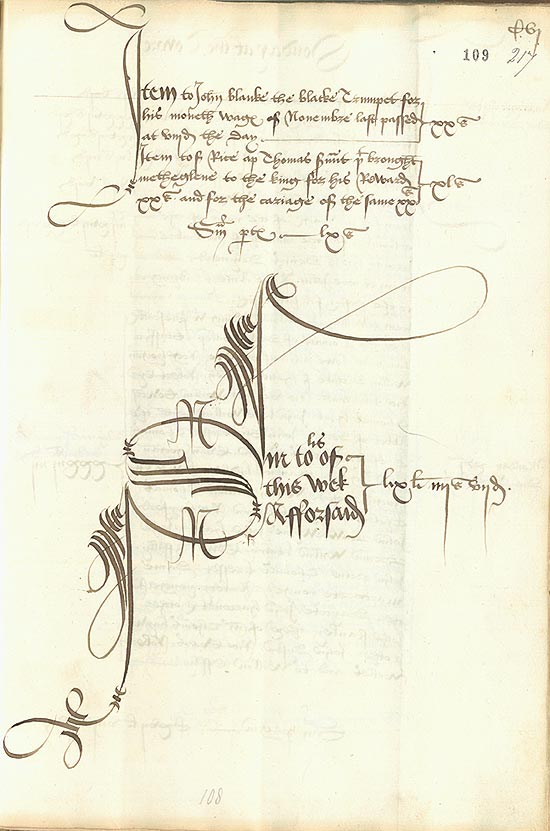

John Blanke was a trumpeter and was hired by Henry VII to play in his court. A surviving document from the accounts of the Treasurer of the Chamber records a payment of 20 shillings to “John Blanke the blacke trumpet” as wages for the month of November 1507, with payments of the same amount continuing monthly through the next year. He successfully petitioned Henry VIII for a wage increase.

Dr Sydney Anglo was the first historian to propose that the “blacke trumpet” in the 1507 court accounts was the same as the black man depicted twice in the 1511 Westminster Tournament Roll. He had proposed this in a footnote to his article about The Court Festivals of Henry VII. The Westminster Tournament Roll is an illuminated, 60-foot-long manuscript now held by the College of Arms; it recorded the royal procession to the lavish tournament held on 12 and 13 February 1511 to celebrate the birth of a son, Henry, Duke of Cornwall (d. 23 February 1511), to Catherine and Henry VIII on New Year’s Day 1511. John Blanke is depicted twice, as one of the six trumpeters on horseback in the royal retinue.

The royal trumpeter, John Blanke was known to earn three times the wage of an average servant. A 60-foot-long vellum manuscript commissioned by Henry VIII sees Blanke sitting on a horse, with a trumpet in his hand and a turban around his head.

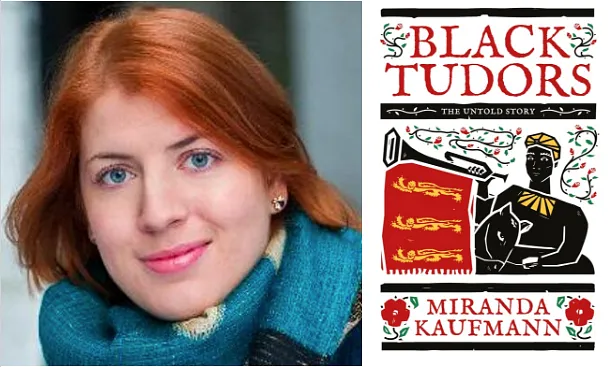

A great example of just how free and ordinary the lives of some of the black Tudors were is illustrated in historian Miranda Kauffman’s book, Black Tudors:The Untold Story published in 2017. Kauffman brings to life the lives of 10 characters, whose skills made them valued, integrated members of their community, they included a silk weaver, salvage diver, merchant and a prostitute.

Nothing screams integration like interracial relationships. Parish records show interracial marriages, for example in 1599 in St Olave Hart Street, John Cathman married Constantia “a black woman and servant”. A bit later, James Curres, “a moore Christian”, married Margaret Person, a maid.

But how did we come to be here you wonder?

Well, a great deal came via Portuguese trading ships with enslaved Africans onboard, others came with merchants or from captured Spanish ships. England had not yet established itself as a superpower, coloniser. The superpowers of the time were Portugal and Spain. In 1562, Captain John Hawkins, on behalf of Elizabeth I made his first slaving voyage to Africa. Making a further three voyages over six years. It was not until the early 1600s that they really ramped up their slaving enterprise. On England soil, however, it was forbidden by law for anyone to be a slave.

London could definitely be seen as a metropolis, even then it was the most diverse city in England. Immigrants from France, Spain, Italy and Portugal came to London in their thousands, with approximately 1000 Africans living across England. The city grew from 50,000 in 1500 to 200,000 a century later. To state the obvious, assimilation was easier for the Europeans, the Africans were an easy target for a city under strain. Tolerance towards black people became a notable issue as documented in the Cecil papers in 1601.

“The queen is discontented at the great numbers of ‘negars and blackamoores’ which are crept into the realm since the troubles between her Highness and the King of Spain, and are fostered here to the annoyance of her own people.”

We did not come to be here by choice, but we were definitely here and present in society nonetheless. Our presence grew to approximately 20,000 by the 1800s, largely due to the end of slavery. There were even prominent and celebrated figures such as Cesar Picton, Olaudah Equiano and Ignatius Sancho who enjoyed wealth and influence. To say it is time to change the narrative of this nation’s history is an understatement. The omission of the greater story is damaging and deliberate.

When it comes down to it, the onus is on us. We need to make sure we fill in the gaps or craters and tell the story like it really is.”

o0o

Miranda Kaufmann is a Senior Research Fellow at the University of London’s Institute of Commonwealth Studies. Her first book, Black Tudors, was shortlisted for the Wolfson History Prize 2018. She has appeared on Sky News, the BBC and Al Jazeera, and she’s written for The Times, Guardian and BBC History Magazine. She lives in Pontblyddyn in North Wales

The Men and Women featured in the book

Black Tudors: The Untold Story

JOHN BLANKE, the royal trumpeter

The two images of the court trumpeter John Blanke in the Westminster Tournament Roll of 1511 comprise the only known portrait of a Black Tudor. He was present at the court of Henry VII from at least 1507, and may have arrived with Katherine of Aragon in 1501, when she came from Spain to marry Henry VIII’s older brother, Prince Arthur. In 1509 he performed at both Henry VII’s funeral and Henry VIII’s coronation. He was paid wages and successfully petitioned the new king for a pay rise. He married in 1512, and was given a wedding present by Henry VIII, but after that he disappears from the records…

JACQUES FRANCIS, the salvage diver

An expert swimmer and diver, both skills common to his native land, but extremely rare in Tudor England, Jacques Francis was part of a team hired to salvage guns from the wreck of the Mary Rose in 1546. When his Venetian master, Peter Paulo Corsi, was accused of theft by a consortium of Italian merchants based in Southampton, Francis became the first known African to give evidence in an English court of law.

DIEGO, the circumnavigator

Diego ran through gunshot in his eagerness to be taken aboard Francis Drake’s ship when it docked at Nombre de Dios in Panama in 1572. He forged an alliance between the English and the local Cimarrons (Africans who had escaped their Spanish captors to found their own settlements) that resulted in the capture of over 150,000 pesos of Spanish silver and gold. Following this lucrative adventure, Diego returned to Plymouth with Drake, whence they set sail together again once more to circumnavigate the globe in 1577 on the Golden Hinde. He was with Drake when he passed through the straits of Magellan, raided South America and laid claim to California in the name of Elizabeth I in 1579. Diego died near the Moluccas of an arrow wound sustained after a fight a year earlier with the Araucanians, who lived on Mocha island off the coast of Chile.

EDWARD SWARTHYE, the porter

In 1596, Edward Swarthye whipped John Guye, the future first governor of Newfoundland. They were both servants in the Gloucestershire household of Sir Edward Wynter: Guye managed the iron works, while Swarthye was the porter. Swarthye had likely been brought home by Wynter after he captained the Aid on Francis Drake’s Caribbean raid of 1585-6, one of many Africans who fled their Spanish enslavers to join the English. The whipping was just one incident in an ongoing family feud between the Wynters and their neighbours the Buckes. Edward Swarthye appeared as a witness in the ensuing court case of 1597, his testimony confirming that he, a Black Tudor, had whipped a white man before a crowd assembled in the Great Hall at the Wynter’s home, White Cross Manor.

REASONABLE BLACKMAN, the silk weaver

Reasonable Blackman made an independent living as a silk weaver living in Southwark c. 1579-1592. The silk industry was new to England but its products were the height of fashion. He had probably arrived in London from the Netherlands, which had both a sizeable African population and was a known centre for cloth manufacture. He had a family of at least three children, but sadly lost a daughter, Jane, and a son, Edmund, to the plague that struck London in 1592.

MARY FILLIS, the Moroccan convert

Mary Fillis was the daughter of Fillis of Morisco, a Moroccan basket weaver and shovel maker. She came to London c. 1583-4 where she became a servant to John Barker, a merchant and sometime factor for the Earl of Leicester. By the time of her baptism in the summer of 1597, she was working for a seamstress from East Smithfield named Millicent Porter. Porter died on 28 June 1599 but we do not know what became of Fillis. She was however present in London during a period which saw a succession of ambassadors arriving in England from her native land in order to negotiate alliances against the common enemy: Spain.

DEDERI JAQUOAH, the prince of River Cestos

Jaquoah was the son of King Caddi-biah, who ruled a kingdom in modern-day Liberia known for its meleguetta pepper or ‘grains of paradise’ and ivory. He arrived in England aboard the Abigail in the autumn of 1610, and was baptised in the City of London church of St. Mildred’s Poultry on New Year’s Day 1611. He spent two years in England with John Davies, the leading Guinea merchant of the day, before returning home. In 1615, he received a delegation of East India Company merchants en route to Bantam. They reported that he spoke good English and made ‘great proffers and promises of trade’.

Worth looking at the transcript of this podcast, where Miranda Kaufman is part of the panel, and she refers to documentation which confirm payments to a number of African people for various tasks, as well as the confirmation in Registers such as Births, Marriages and Deaths.

JOHN ANTHONY, mariner of Dover

John Anthony was a sailor who almost certainly came to England with the pirate Sir Henry Mainwaring. In 1619 he was employed aboard The Silver Falcon on a voyage to Virginia. Had all gone according to plan he, a free, waged, sailor, would have been the first African to arrive in an English colony in mainland North America. However the ship only made it as far as Bermuda, where it acquired a cargo of tobacco in dubious circumstances, before docking unexpectedly in the Netherlands. A bitter dispute followed between the owner of the ship, Lord Zouche, and the principal merchant in the venture. This held up the payment of John Anthony’s wages but after petitioning Lord Zouche, he eventually received payment with interest in the spring of 1620.

ANNE COBBIE, the tawny Moor with soft skin

Anne Cobbie was a prostitute who worked in the parish of St. Clement Danes, Westminster, in the 1620s. It was said that men would rather give her a gold coin worth 22 shillings ‘to lie with her’ than another woman five shillings ‘because of her soft skin’. She was one of ten women cited when the couple who owned the brothel where she worked were brought before the Westminster Sessions Court in 1626. The action was brought by one Clement Edwards, a clergyman from Leistershire whose wife had left him to work in the Bankes’ establishment. Anne Cobbie is exceptional: there is actually more evidence of African men visiting English prostitutes than vice versa at this time.

CATTELENA OF ALMONDSBURY, independent single woman

One of a number of Africans recorded in rural locations, Cattelena lived in the small Gloucestershire village of Almondsbury, not far from Bristol, until her death in 1625. An inventory survives of the goods she owned. Her most valuable possession was a cow, which not only supplied her with milk and butter but allowed her to profit from selling these products to her neighbours. No furniture is listed, which suggests she may have shared her home, perhaps with Helen Ford, the widow who administered her estate. Her possessions, from her cooking utensils to her table cloth, each tell us something of her life, but the fact that she had them at all tells us even more. Africans in England, like Cattelena, were not owned, but possessed property themselves.

http://www.mirandakaufmann.com

Writing Our Legacy

Writing Our Legacy is an organisation whose aim is to raise awareness of the contributions of Black and Ethnic Minority (BME) writers, poets, playwrights and authors born, living or connected to Sussex and the South East. We employ Mosaic charity’s definition of Black to be ‘Black people’ and ‘mixed-parentage people’ including all those people whose ancestral origins are African, Asian, Caribbean, Chinese, Middle Eastern, North African, Romany, the indigenous peoples of the South Pacific islands, the American continents, Australia and New Zealand. We run events across Sussex and the South East that showcase emerging and established BME writers and provide professional development and networking opportunities.

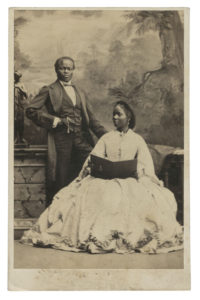

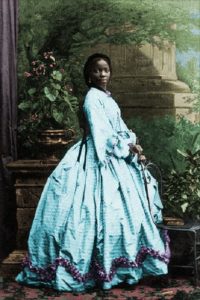

Sarah Forbes Bonetta

“There is a deep sadness and hidden trauma in the eyes of Sarah Forbes Bonetta in every photo I have seen of her. Omoba Aina, as she was born, or Sally, as Queen Victoria nicknamed her. She was named after her rescuers ship, HMS Bonetta.

Sarah was born in 1843, a West African Egbado princess of the Yoruba people. At age five her village was attacked and her parents killed. Shortly before she was due to be sacrificed in the court of King Ghezo, she was saved by a British Captain, Captain Frederick E. Forbes of the Royal Navy who suggested she be offered as a present to Queen Victoria.

Transported to England, Sarah lived at first with Captain Forbes’s family. On 9 November, she was taken to Windsor Castle and received by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. The Queen was so impressed with Sarah that she paid for her education and met with her on several occasions, even writing about her in her journal.

Sarah was plagued by fragile health. In 1851 she returned to Africa to attend the Female Institution in Freetown, Sierra Leone. At 12 years old, Queen Victoria commanded that Sarah return to England and was placed under the charge of Mr and Mrs Schon at Chatham.

Growing up, Sarah spent a lot of time visiting Queen Victoria and their household at Windsor Castle and was close friends with her daughter Princess Alice. Queen Victoria was impressed with Sarah’s natural regal manner and her academic abilities and knowledge of literature, art and music.

In a very modern way, Sarah had a career, training as a teacher so that was one thing she enjoyed. But the Queen made sure she understood that she must marry in order to be maintained in the manner in which she was accustomed.

An appropriate suitor was found: Captain James Pinson Labulo Davies, a wealthy Yoruba businessman. Of course she had to marry someone who was African like her. Sarah refused and was sent to live in Brighton, with two elderly ladies whose house she described as a “desolate little pig sty”. Unhappy with the situation, Sarah felt she had not choice but to accept the offer.

Following their wedding in 1862, the couple lived briefly in Brighton’s Seven Dials at 17 Clifton Hill. They then moved to Lagos and had three children: Victoria Davies was born in 1863, followed by Arthur Davies in 1871 and Stella Davies in 1873. The first born was named after Queen Victoria, who was given an annuity by the Queen and continued to visit the royal household throughout her life.

Sarah died on 15 August 1880 in the city of Funchal, the capital of Madeira Island, a Portuguese island in the Atlantic ocean. Her husband erected a granite obelisk-shaped monument more than eight feet high in her memory at Ijon in Western Lagos, where he had started a cocoa farm.

The inscription on the obelisk reads:

IN MEMORY OF PRINCESS SARAH FORBES BONETTA

WIFE OF THE HON J.P.L. DAVIES WHO DEPARTED THIS LIFE AT MADEIRA AUGUST 15TH 1880

AGED 37 YEARS

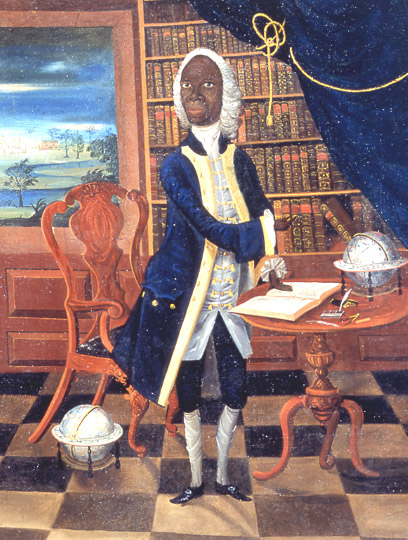

Francis Williams

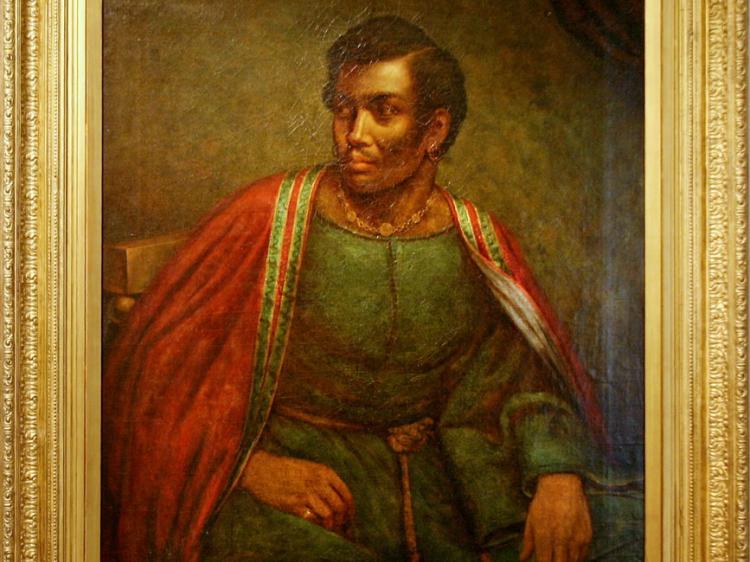

Francis Williams, an Afro-Caribbean British scholar and poet. A member of a property-owning Afro-Jamaican family, he took British citizenship in 1723.

This full-length portrait shows the Jamaican scholar and writer Francis Williams. It was painted around 1745 by an unknown artist who was most likely based in Jamaica – through the window we see (probably) Spanish Town, the beach and bright azure sky. The rest of the picture copies the style of formal European portraits, which the artist may have seen in the form of printed reproductions.

Francis Williams was born in Jamaica in around 1692 to John and Dorothy Williams. Francis’s exact date of birth is not known, but when he died in 1762 he was reportedly ‘aged seventy or thereabouts’. John Williams was not emancipated from slavery until 1697 – if Francis was born before then, he was born into slavery.

Following his emancipation, John Williams became a successful and wealthy merchant, buying land and slaves of his own. Francis had two elder brothers, John and Thomas, and a sister, Lucretia. As emancipated slaves, the Williams family were free to live and work, but they were not automatically granted the same legal and civil rights as white Jamaicans. In February 1708 John Williams succeeded in having a special local law passed that granted him the right to trial by jury, and prevented slaves from testifying against him. When John Williams died in 1723, his estate included land, slaves and debts owed to him by prominent members of Jamaican society. John Williams’ independent wealth secured an education for Francis and his brothers.

Almost everything we know about Francis comes from a book called the History of Jamaica, written by Edward Long and published in London in 1774. Long was not an impartial biographer, and it is likely that his racism led to him underplaying Francis’s achievements. The book describes Francis as ‘haughty, opinionated … [and with] the highest opinion of his own knowledge’, but this portrait was owned by Long’s descendants until it was given to the V&A.

While we might not trust all of what Long says about Francis’s education, he certainly became a member of Lincoln’s Inn (one of the professional associations for barristers) in London on 8 August 1721. Francis then returned to Jamaica shortly after the death of his father. It appears that he spent the rest of his life there; he ran a school in Spanish Town, teaching Black students reading, writing, Latin and mathematics.

Today, Francis William’s status is made problematic by the fact that he and his family profited from the labour of enslaved Africans. However, his existence as a rich, educated free Black man who wrote Latin poetry was a direct challenge to the theories of white supremacy that underpinned the transatlantic slave trade.

Ignatius Sancho

Painted by Thomas Gainsborough

Ignatius Sancho is the first known person of African descent to vote in a British general election. As an independent male property owner, with a house and grocery shop on Charles Street, he had the right to cast his vote for the Westminster Members of Parliament in the 1774 and 1780 elections.

A British abolitionist, writer and composer. Born on a slave ship in the Atlantic, Sancho was sold into slavery in the Spanish colony of New Granada. After his parents died, Sancho’s owner took the two-year-old orphan to England and gifted him to three Greenwich sisters, where he remained their slave for eighteen years. Unable to bear being a servant to them, Sancho ran away to the Montagu House, whose owner had taught him how to read and encouraged Sancho’s budding interest in literature. After spending some time as a servant in the household, Sancho left and started his own business as a shopkeeper, while also starting to write and publish various essays, plays and books.

Sancho quickly became involved in the nascent British abolitionist movement, which sought to outlaw both the slave trade and the institution of slavery itself, and he quickly became one of the most devoted supporters of the movement. Sancho’s status as a male property-owner meant he was legally qualified to vote in a general-election, a right he exercised in 1774 and 1780, becoming the first known Black Briton to have voted in Britain. Gaining fame in Britain as “the extraordinary Negro”, to British abolitionists, Sancho became a symbol of the humanity of Africans and the immorality of the slave trade and slavery. Sancho died in 1780, with his The Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho, an African, edited and published two years after his death, being one of the earliest accounts of African slavery written in English from a first-hand experience.

On 17 December 1758[10] he married a West Indian woman, Anne Osborne, becoming a devoted husband and father. They had seven children: Frances Joanna, Ann Alice, Elizabeth Bruce, Jonathan William, Lydia, Katherine Margaret, and William Leach Osborne.[2] Around the time of the birth of their third child, Sancho became a valet to George Montagu, the son-in-law of his previous patron.[5] Sancho remained a valet until 1773.[5]

In 1768, British artist Thomas Gainsborough painted a portrait of Sancho at the same time as the Duchess of Montagu sat for her portrait by Gainsborough as well.[1][notes 1] By the late 1760s, Sancho had already become well accomplished and was considered by many to be a man of refinement.[5] In 1766, at the height of the debate about slavery, Sancho wrote to Anglo-Irish novelist Laurence Sterne[11] encouraging the famous writer to use his pen to lobby for the abolition of the slave trade.[12]

Ignatius Sancho died from the effects of gout on 14 December 1780 and was buried in the churchyard of St Margaret’s, Westminster. There is no memorial at the church, as the grave stones (which lie flat) in the churchyard were covered over with grass in 1880 and no inscription was found for him when a record was made of the existing epitaphs.[22] He was the first person of African descent known to be given an obituary in the British press.[22]

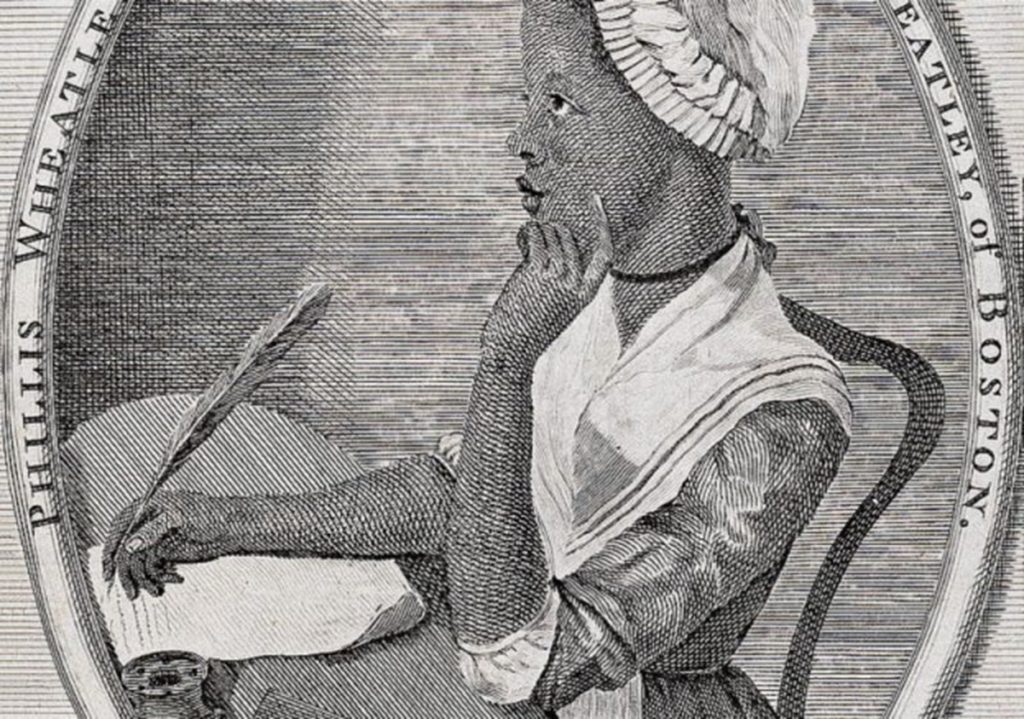

Phylis Wheatley

(c. 1753 – December 5, 1784) was an American author who was the first African-American author of a published book of poetry.[2][3] Born in West Africa, she was sold into slavery at the age of seven or eight and transported to North America, where she was bought by the Wheatley family of Boston. After she learned to read and write, they encouraged her poetry when they saw her talent.

On a 1773 trip to London with her master’s son, seeking publication of her work, Wheatley met prominent people who became patrons. The publication in London of her Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral on September 1, 1773, brought her fame both in England and the American colonies. Figures such as George Washington praised her work.[4] A few years later, African-American poet Jupiter Hammon praised her work in a poem of his own.

Wheatley was emancipated by her masters shortly after the publication of her book.[5] They soon died, and she married poor grocer John Peters, lost three children, and died in poverty and obscurity at the age of 31.

There were many more people that i discovered in my searches, but too many to list here in one article. The references below, give your links to a variety of website, with lots of useful and interesting information, and in doing so, give you other websites to explore. I hope you found this interesting too, although i was only able to capture small pieces of information about a selection of individuals for the purposes of the podcast topic. I will be doing another podcast on this topic in October, which is the UK Black History Month.

Happy Researching.

YouTube video of the podcast:-

Ivy Barrow

14/02/22

Reference Sources

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory/early_times/moors.htm

https://www.iamhistory.co.uk/blackhistory/black-tudors-in-art

https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/articles/z8gpm39

https://tudorfair.com/blogs/the-tudor-fair-blog/black-tudor-history

http://www.mirandakaufmann.com/uploads/1/2/2/5/12258270/bbchmblacktudors.pdf

https://oneworld-publications.com/miranda-kaufmann.html

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory/early_times/blanke.htm

https://www.pushblack.us/news/black-man-1566-whipped-white-man-what-happened-next

https://stuartsworkbench.blogspot.com/2012/11/john-blanke.html

https://thinkafrica.net/jacques-francis/

https://www.black-history.org.uk/19th-century/sarah-forbes-bonetta-1843-1880/

Royal Pavilion & Museums collections, Brighton Gazette August 1862.

http://writingourlegacy.org.uk Author of the article I included is Amy Zamarripa Solis

https://whitchurchsilkmill.org.uk/the-story-of-reasonable-blackman/

https://greenhare.co.uk/history-ignatius-sancho/

https://www.black-history.org.uk/19th-century/sarah-forbes-bonetta-1843-1880/

Royal Pavilion & Museums collections, Brighton Gazette August 1862.

https://www.simon-hartman.com/post/the-presence-of-africans-in-european-history

https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/francis-williams-a-portrait-of-a-writer

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ignatius_Sancho

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phillis_Wheatley